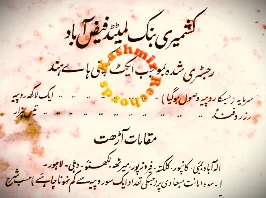

A recent find by Kashmir Rechords—a rare Urdu directory of Kashmiri Pandits from 1924-1934—has uncovered a forgotten chapter of history, revealing the existence of a “Fire Temple” dedicated to Swami Dhooni Sahib near Gujrat, Pakistan. Built by the Kashmiri Pandit community in Qilladar (Killadar) around 1884, this temple and adjacent school embody their devotion, cultural resilience, and educational values.

(By:Dr.Rajesh Bhat)*

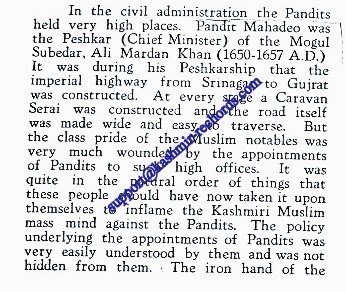

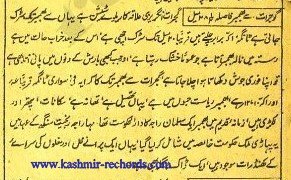

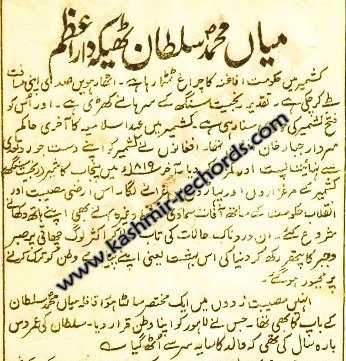

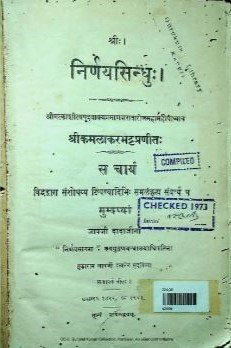

The recent discovery of a rare Urdu directory of Kashmiri Pandits from British India, dated between 1924 and 1934, has revealed a hidden chapter of history, bringing to light an extraordinary story of cultural resilience and devotion. This directory not only showcases the lives of Kashmiri Pandits across British India but also unveils the existence of a unique Temple, built in memory of the revered mystic Swami Dhooni Sahib. This structure stands as a symbol of the community’s enduring spirit and reverence, located near Gujrat city in what is now Pakistan.

Historical Significance of the Dhooni Temple

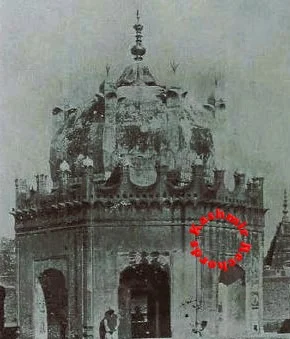

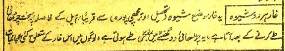

The Dhooni Sahib Temple, or what they now call, “Fire Temple,” is believed to have been constructed around 1884 in the town of Qilladar (also known as Killadar) in Gujrat, Punjab, Pakistan. Adjacent to this sacred structure, the Kashmiri Pandit community also built a school and an inn for travellers—a testament to their commitment to education and hospitality. The temple’s location and purpose hold unique cultural importance, as it was built on a site with natural flames emerging from the earth, which possibly drew mystics like Swami Dhooni Sahib for worship.

In addition to its religious significance, the site highlights the cohesive nature of the Kashmiri Pandit community in preserving their heritage. Despite being scattered across British India, these families maintained strong ties to their roots, even constructing a temple and school far from their homeland to honor their values and spiritual mentors.

Qilladar: A Hub of Heritage and Influence

Qilladar, a town in Gujrat District near the Upper Jhelum Canal, became a cultural and spiritual centre for the Kashmiri Pandits in British India. Its strategic location—close to major cities like Amritsar, Lahore, Sialkot and Jammu—made it a meeting point for communities and travellers alike. The town was historically significant as some of the decedents of Dewan Dena Nath, a prominent Kashmiri Pandit figure in the Sikh Empire’s durbar, continued his legacy of community building by constructing the Fire Temple in Dhooni Sahib’s honor.

Under the governance of Sir Charles Umpherston Aitchinson, then Lt. Governor of Punjab, the Kashmiri Pandit community received support to build the temple. Dewan Dena Nath’s family lineage and the Madan clan, notable Kashmiri Pandits in the region, were instrumental in maintaining the temple and the school complex, which fostered learning and faith for future generations.

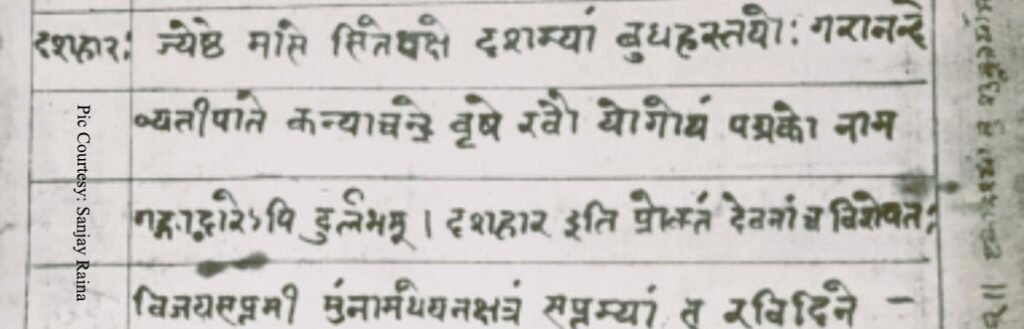

Legends and Myths of the `Fire’ Temple

The Dhooni Temple, according to local traditions, is said to be rooted in mystical significance. Stories speak of a perpetual flame emerging naturally from the earth, which may have inspired Dhooni Sahib and other mystics to consider it a sacred site. Sadly, this remarkable heritage site now suffers from encroachment and deterioration, with remnants barely hinting at its former grandeur.

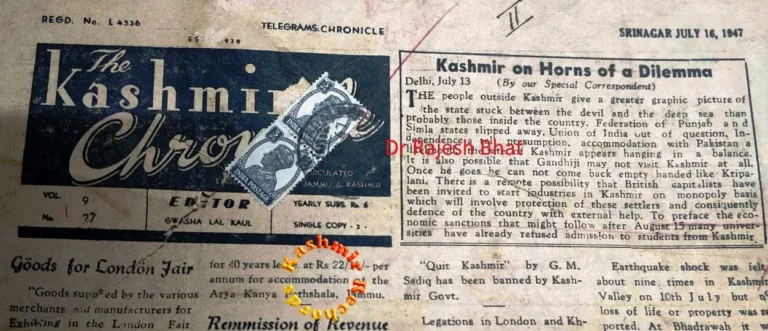

Today, videos and photos of the temple(s) circulated by local Pakistani content creators have sparked interest, though limited historical knowledge has left gaps in understanding the temple’s origin. Misinterpretations have even led to speculation that it might be a Sun Temple, as the word “Dhooni” relates to fire in Hindi. This post of Kashmir Rechords thus aims to dispel these myths by bringing clarity to the temple’s history and role in the Kashmiri Pandit tradition.

Legacy in Peril: The Struggle to Preserve a Heritage Site

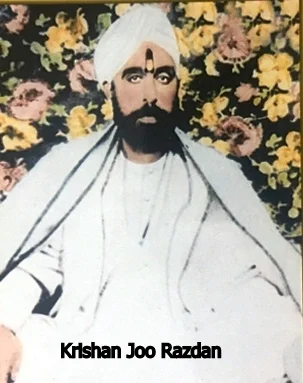

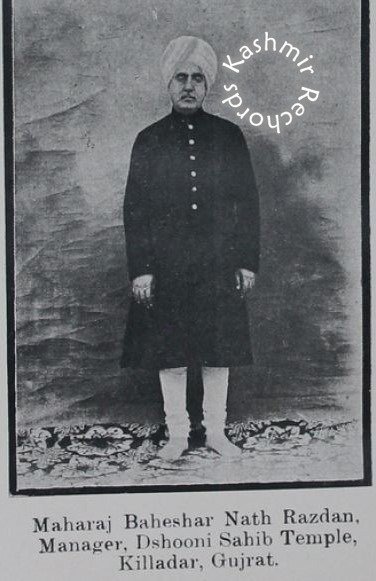

The once-vibrant structures of the Dhooni Sahib Temple and the school complex now stand in a state of disrepair. Maharaj Baheshar Nath Razdan, a Kashmiri Pandit who managed the temple, school, and inn, dedicated years of service to preserving the sanctity of the site. However, the passing of time and the division wrought by the 1947 partition has left this cultural gem largely abandoned.

Although local YouTubers and enthusiasts have made efforts to document the site, the absence of comprehensive historical data has hindered a true appreciation of its value. Kashmir Rechords thus hopes to reconstruct the story of the Fire Temple, school, and the surrounding community to share it with future generations, ensuring that this chapter of Kashmiri Pandit heritage remains in collective memory.

Rediscovering the Past for Future Generations

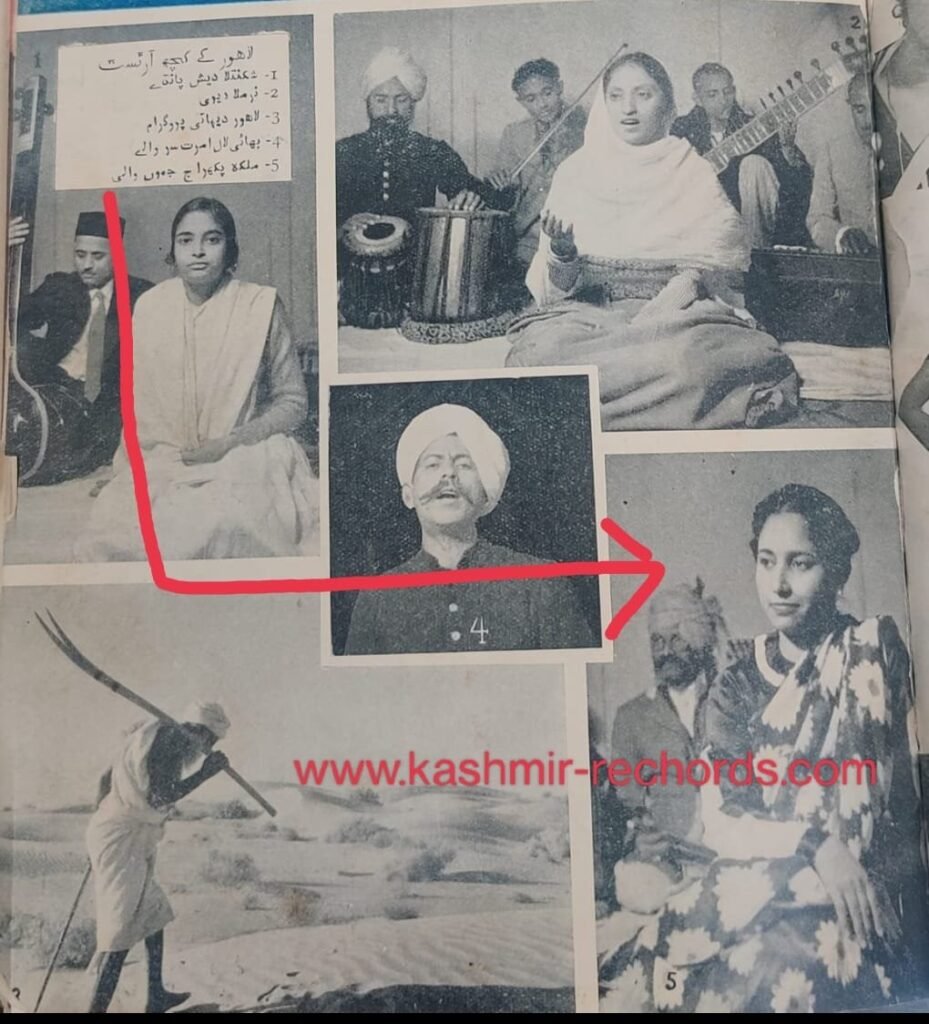

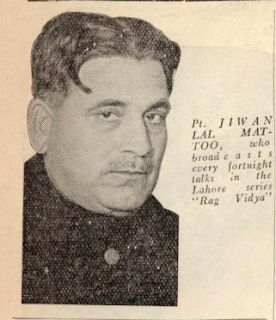

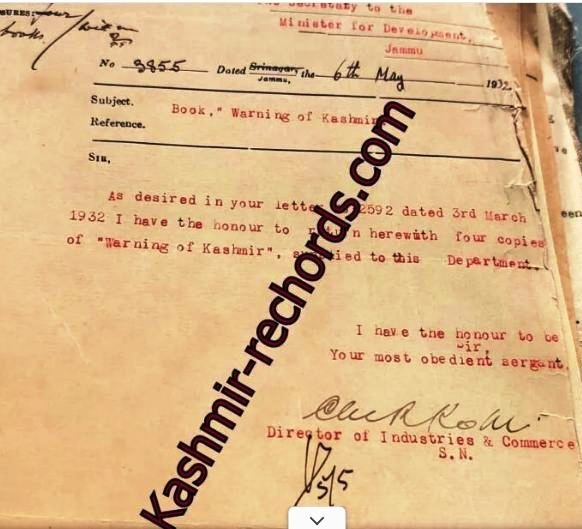

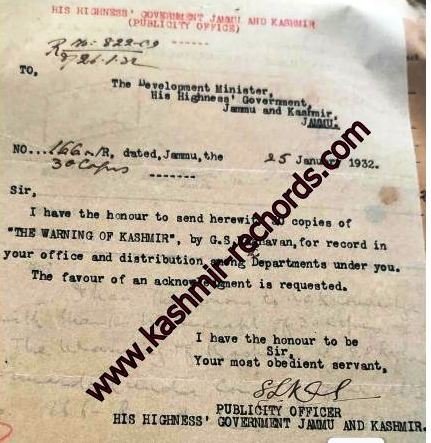

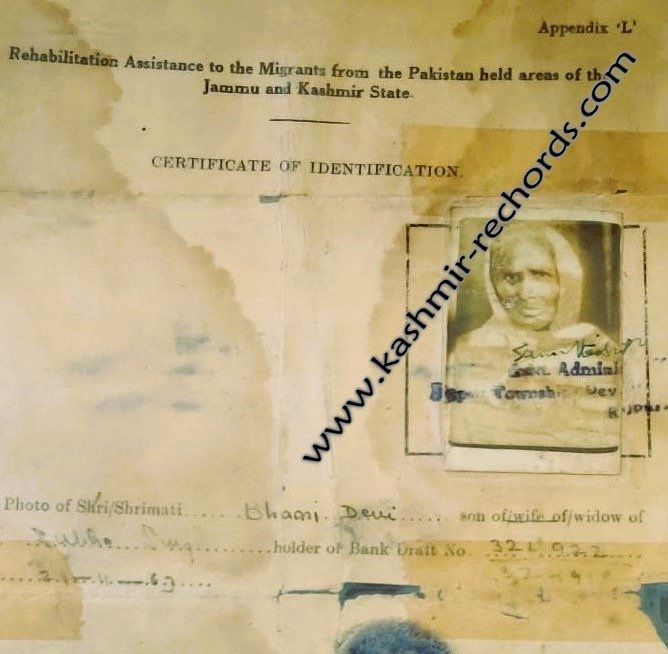

With the Urdu directory of Kashmiri Pandits from 1924–1934 now in hand, Kashmir Rechords is embarking on a journey to uncover and share further insights about Kashmiri Pandit life and legacy across British India. This historical document, filled with photographs, family details, and anecdotes, is a window into a rich heritage that extends beyond the geographical boundaries of Kashmir.

Through ongoing research and publications, Kashmir Rechords aspires to illuminate more such hidden stories. The Dhooni Saheb Temple in Qilladar, Gujrat, serves not only as a reminder of Kashmiri Pandit faith and resilience but also as an inspiration for preserving cultural memory, honoring the past while paving the way for future generations to rediscover and cherish their heritage.

*Dr. Rajesh Bhat is a Kashmir-born Journalist, Writer and Researcher; formerly associated with Daily Excelsior J&K and The Tribune, Chandīgarh. He is the Author of Radio Kashmir in Times of Peace & War. He can be reached at: raajbhat@gmail.com

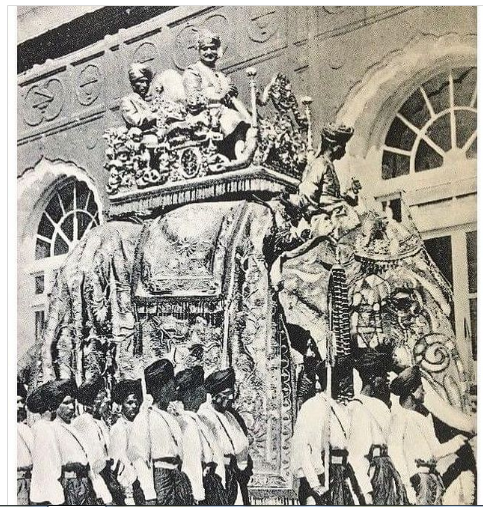

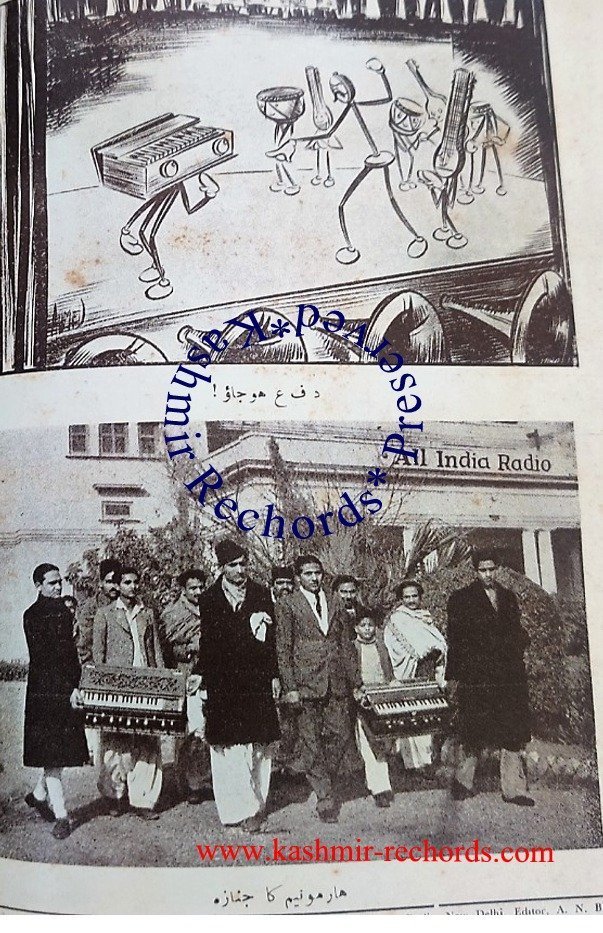

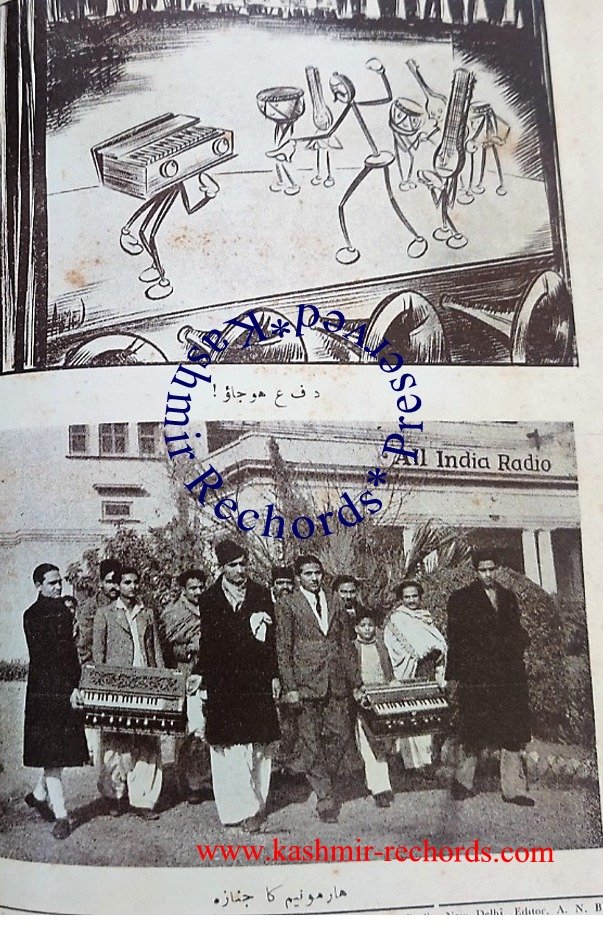

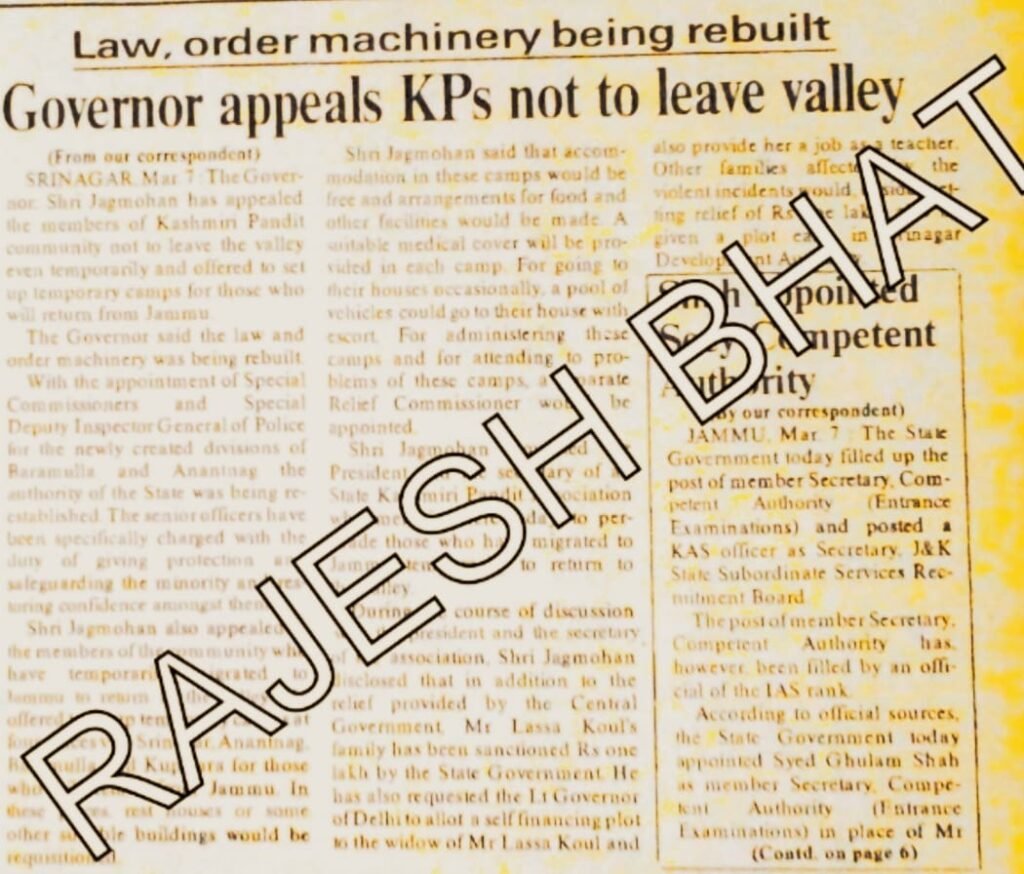

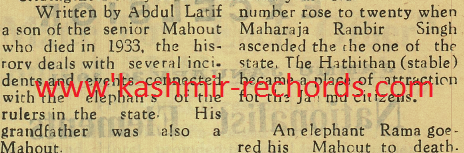

Excerpts of a Book Review of “History of Elephants in Jammu and Kashmir”, published in Daily Excelsior on January 30, 1971.

Excerpts of a Book Review of “History of Elephants in Jammu and Kashmir”, published in Daily Excelsior on January 30, 1971.