(Kashmir Rechords Exclusive)

Despite multiple policy pushes, emotional appeals and community-driven initiatives, the return of Kashmiri Pandits to their homeland has remained elusive for over three decades. At the heart of this long delay lies a bitter reality—moves for return have been consistently blocked or derailed not just by security threats or political inertia, but also by resistance from within the community and opposition from the majority in the Valley. This is a story of missed chances, internal divides and quiet sabotage.

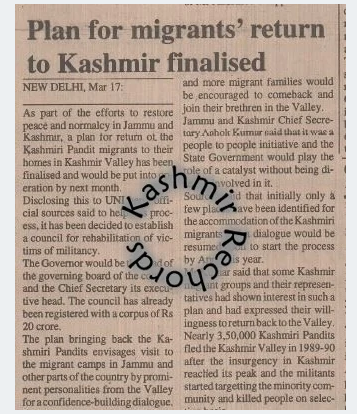

1996: The First Major Effort Thwarted by Community Opposition

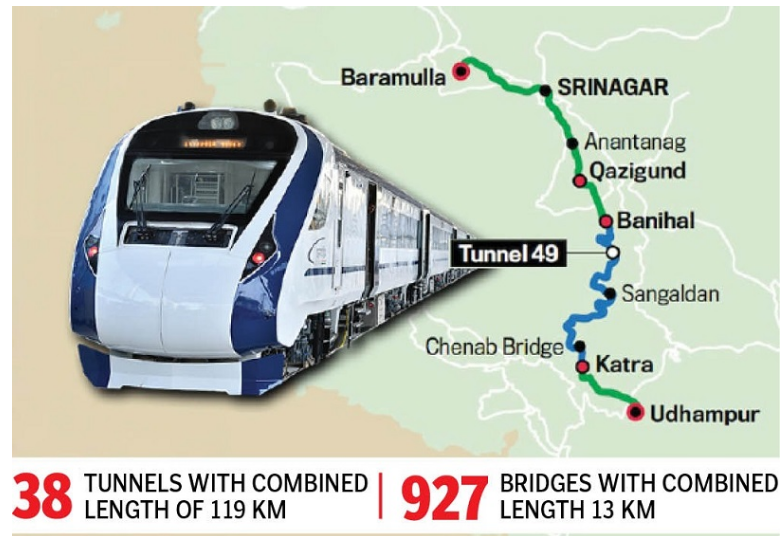

In early 1996, the Indian government, under Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao and J&K Governor General K.V. Krishna Rao, drew up a concrete plan for the return of Kashmiri Pandits. Key areas in the Valley—Pulwama, Baramulla, Anantnag, Bandipora and Srinagar—were identified for phased rehabilitation.

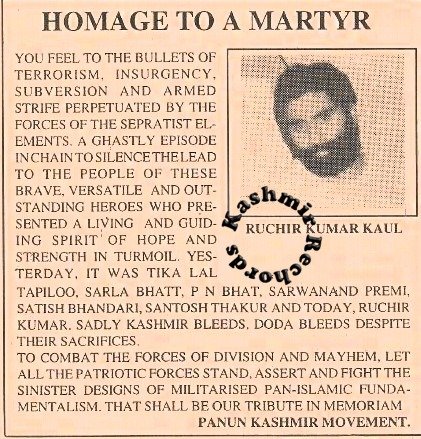

Yet, just as the initiative was about to roll out, it was fiercely rejected by Kashmiri Pandit organizations. Groups like Panun Kashmir, ASKPC and the Kashmiri Samiti Delhi dismissed the plan as“ vague, unsafe and ill-timed”. Some leaders went as far as issuing directives to avoid contact with the Valley’s Muslim majority.

Despite the Central Government’s commitment, resistance from within the displaced community derailed the plan—a stunning irony for a population longing for return.

Local Hostility: Silent but Persistent Opposition from the Valley

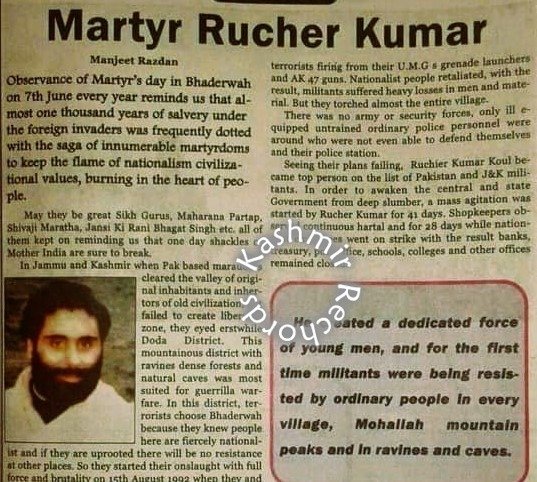

While Kashmiri civil society has occasionally expressed symbolic solidarity, ground realities suggest a deep-seated resistance to the return of Pandits. Incidents of violence whenever return was even discussed—particularly in the early 2000s—sent a chilling message.

During L.K. Advani’s tenure as Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister (1999–2004), the idea of return of Kashmiri Pandits was revived—but with even more caution. Advani, aware of the emotional and strategic gravity of Pandit rehabilitation, initiated informal consultations. But again, a series of militant attacks on returning Pandits in the Valley derailed any forward movement.

Security threats once more became the convenient justification for indefinite postponement.

In 2003, and again during later attempts, local militant elements made it clear that they would not tolerate reintegration, especially without full-scale political concessions. Many Pandits and observers even to this day believe that the fear of being unaccepted or targeted again continues to be a major deterrent.

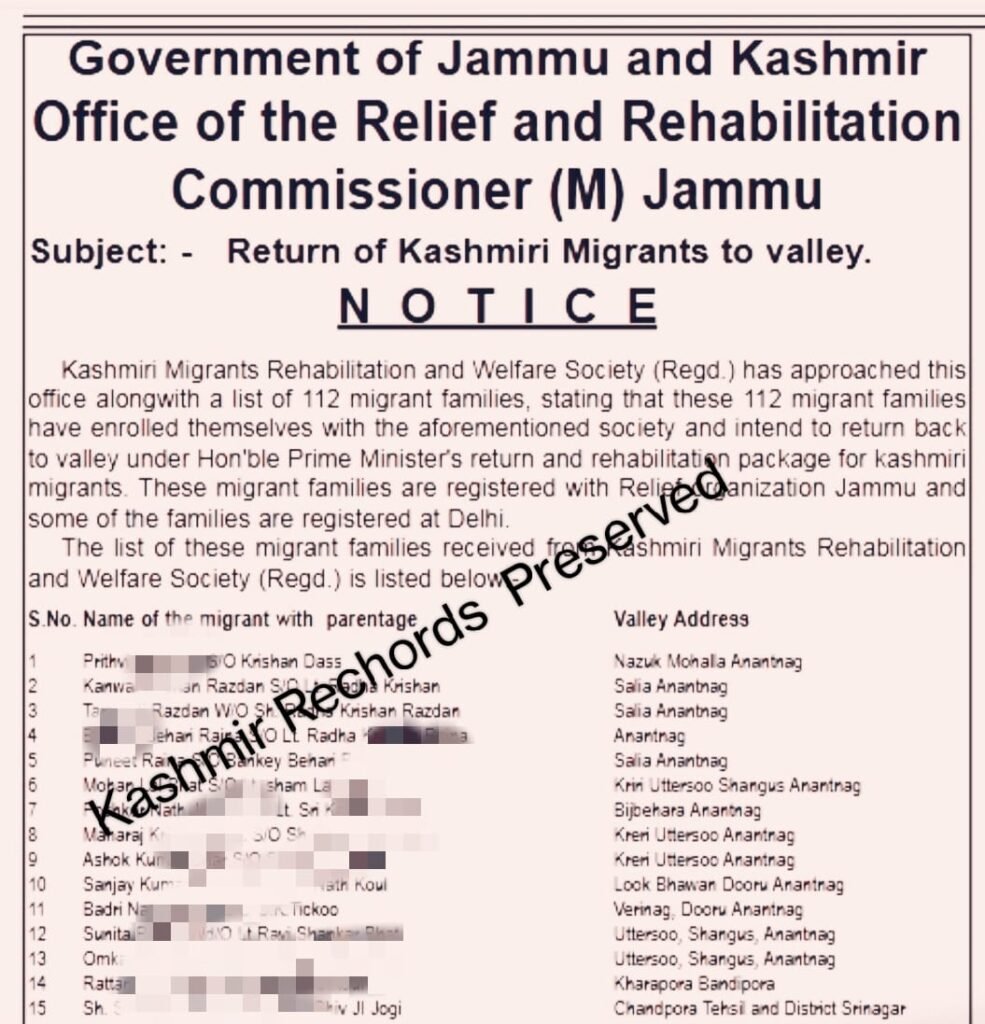

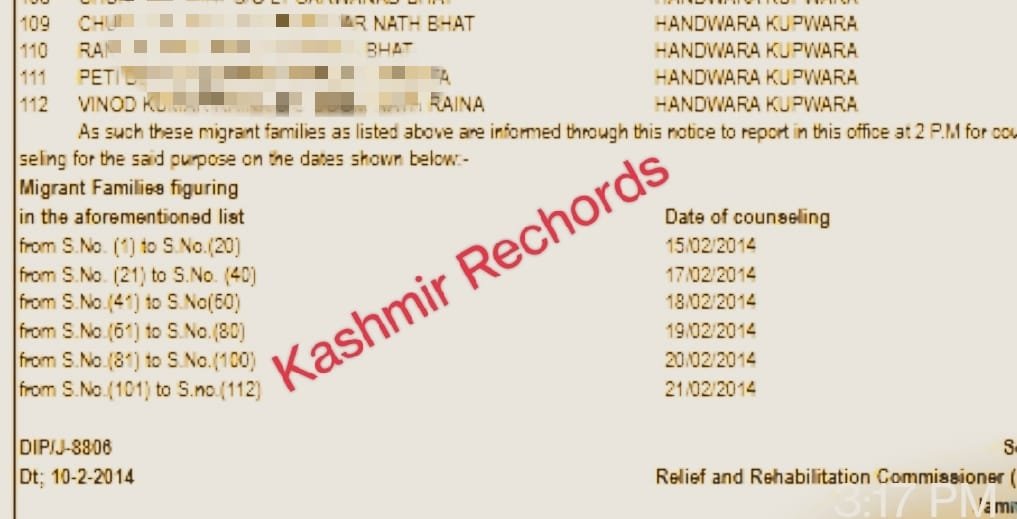

2014: Bureaucratic Sabotage in the Name of Transparency

A fresh attempt was again made in 2014 when 112 Kashmiri Pandit families under the banner Kashmiri Migrants Rehabilitation and Welfare Society ( Regd) expressed their willingness to return under Prime Minister’s rehabilitation package. But the J&K administration, in what many saw as a calculated move, published the personal details of these families in local newspapers with ominous consequences.

This public disclosure made the volunteers vulnerable to threats and intimidated others who might have followed the suit. While disguised as a formal “notice,” it was inadvertently or otherwise a bureaucratic sabotage of a fragile and courageous initiative.

2019: Internal Division Replays the 1996 Script

In 2019, the J&K Peace Forum submitted a list of 419 families volunteering to return. Yet again, sections of the Pandit leadership opposed the initiative. A joint statement from several community organizations denounced the plan, echoing the language of 1996. The unfortunate events have shown that Pandit leaders have behaved sometimes in a narcissistic way and at other times they have shown themselves as bereft of the vision and on many occasions, their independence and the thought processes appear to have been hijacked by the dispensations at both State and Centre levels.

Rather than welcoming the voluntary move of some of those who intended to go back to their roots, the old ideological fault lines resurface time and again—those demanding a separate homeland refuse to support reintegration within existing demographics.

2025: The Social Media War Further Splits the Return Discourse

Following the 2025 Pahalgam incident, Kashmir-based Dr. Sandeep Mawa launched ‘Aalav’, a campaign pushing for return and justice. Mawa’s team identified temple land grabbers and pushed for legal reclamation.

But rather than rallying behind the effort, a large section of Pandit activists on social media launched a massive campaign against Dr. Mawa, accusing him of going against the “homeland resolution.” While terming him as a controversial'' figure and the guy not to be trusted'', they argued that return should be on their “terms and conditions”.

Role of the State: Apathetic, Reactive and Non-Committal

Beyond community divisions and local opposition, the role of successive governments has been deeply problematic. Whether under Congress, BJP or regional parties, the return of Pandits, over the past, has never moved beyond symbolic speeches, half-hearted schemes and reactive measures.

No government has ever made the return of Pandits a national priority, and many well-documented moves were either abandoned mid-way or quietly buried. Security fears and political cost calculations have taken precedence over justice and restitution.

The Return That Everyone Talks About—But Few Truly Support

Today, many in the Kashmiri Pandit community still dream of return. Yet, every time a door opens, it is quickly slammed shut—by bureaucrats, by fellow Pandits, by Valley actors, or by political leaders unwilling to take risks.

The result is a tragic paradox: a displaced community that longs for home, but is divided on how to get there; a Valley that once celebrated coexistence, but has become hesitant, and at times hostile; and a nation that invokes their pain, but hesitates to heal it.

Until all stakeholders—within the community, within the Valley, and within the State—align with sincerity, the return of Kashmiri Pandits will remain a story of promises made, and promises abandoned.