(Kashmir Rechords Exclusive)

The plight of Kashmiri Pandits has once again resurfaced in Jammu and Kashmir’s political discourse. This time, the infamous Anantnag riots of 1986—often considered the precursor to the mass migration of 1990—are being widely discussed across social media platforms as the 40th anniversary of this deadly communal attack approaches. Despite its significance, the 1986 riots have long been underplayed, leaving many to wonder why such a pivotal moment in history has been largely ignored.

A Sudden Spotlight: Political Motives or Genuine Reflection?

The renewed interest in the 1986 riots by certain political figures raises an obvious question: why now? What has prompted this sudden acknowledgment of past injustices? While answers remain elusive, one undeniable fact is often overlooked—at the time of these attacks, key administrative and law enforcement positions in Jammu and Kashmir were held by Hindus. Yet, despite their influence, they failed to protect Kashmiri Pandits and their sacred shrines.

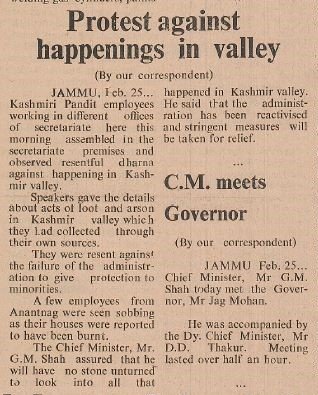

One cannot help but question why such a catastrophe was allowed to unfold when figures such as D.D. Thakur (Deputy Chief Minister), R.K. Thakkar (Chief Secretary), M.M.K. Khajooria (Director General of Police), Dr. A.S. Anand (Chief Justice) and Dr. S.S. Balowria (Divisional Commissioner, Jammu) were in power. Even T.S. Thakur, who later became Chief Justice of India, was then President of the Jammu Bar Association. Yet, a vulnerable minority was left defenceless against organized violence, arson and the desecration of its places of worship.

The Seeds of Exodus: A Planned Onslaught

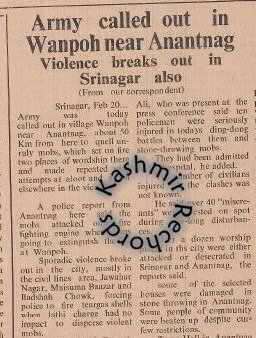

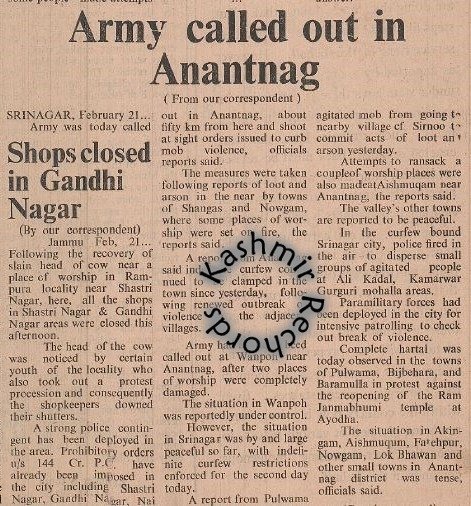

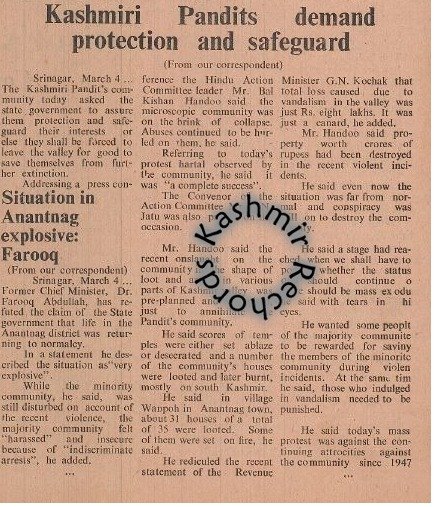

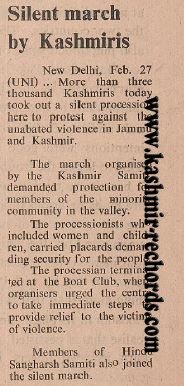

While the 1986 Kashmir riots have largely been underreported. Archival material from some newspapers of that time, who carried the incident and are available with Kashmir Rechords, sheds light on a disturbing pattern. The violence in Kashmir began in Wanpoh village of Anantnag district before spreading rapidly to other nearby villages like Dayalgam and Luk Bhawan, eventually reaching Srinagar. Temples were torched, idols desecrated, businesses looted and homes vandalized. Even after Maha Shivratri on March 8, 1986, the terror did not subside, spreading further to Pulwama, Tral, Sopore and Baramulla.

Interestingly, the tensions did not originate in Kashmir but in Jammu on February 17, 1986, where anti-Hindu and anti-national slogans escalated into violence. Soon, this unrest spilled into Kashmir, targeting Pandit homes, businesses and shrines in what appeared to be a well-coordinated effort rather than spontaneous mob fury.

The Global Trigger: Al-Aqsa Mosque, Ayodhya’s Ram Janmabhoomi

The riots of 1986 were not isolated incidents but were exacerbated by global and national events. The purported desecration of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem on February 3, 1986 had acted as a catalyst, sparking few protests in Kashmir. Religious extremists seized the moment, further fuelling communal tensions in Jammu after two weeks. Simultaneously, the reopening of the Ram Janmabhoomi temple in Ayodhya became another flashpoint for aggression. In the meantime, matters escalated when Chief Minister G.M. Shah’s reported proposal to construct a mosque inside Jammu’s Civil Secretariat ignited further discord.

The ensuing turmoil led to widespread attacks on Hindu-owned businesses and temples across Kashmir, including the burning of the historic Akhara Building Complex in Srinagar. The violence reached such a peak that the Indian Army had to be deployed to restore order, and even the Wills Trophy cricket tournament in Jammu was postponed due to the unrest.

Administrative Lapses, Delayed Justice

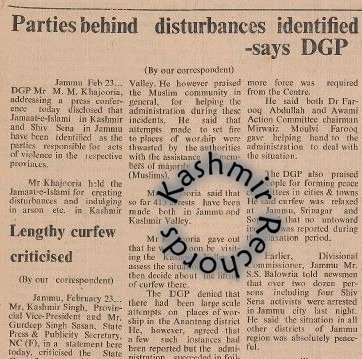

The state government attempted to downplay the scale of destruction. DGP Khajooria blamed groups like Jamaat-e-Islami for violence in Kashmir and Shiv Sena for disturbances in Jammu—claims denied by both. Despite promises, many desecrated temples were never restored, leaving the Kashmiri Pandit community to rebuild them through their own resources.

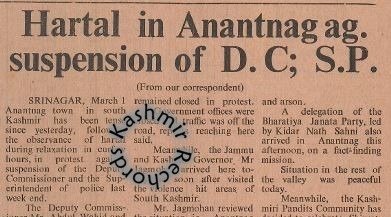

Evidence suggests that elements within the lower bureaucracy were complicit in the violence. On February 27, 1986, the Deputy Commissioner and Superintendent of Police in Anantnag were suspended for negligence, and nine government officials, mostly teachers, were dismissed for aiding rioters. Ironically, instead of condemning the attacks, local residents in Anantnag observed a hartal against the suspension of these officials.

As law and order continued to deteriorate, Governor Jagmohan took charge on March 7, 1986, following the dismissal of G.M. Shah’s Ministry. Jagmohan’s decisive action was widely credited with restoring normalcy. However, history took an ironic turn in 1990 when the same man was vilified—accused of “engineering” the Kashmiri Pandit exodus by politicians who had earlier ignored their plight.

The Aftermath: A Community on the Brink

By the late 1980s, the Kashmiri Pandit community had begun bracing for the worst. Many families started purchasing property in Jammu, particularly in areas like Chinore, Bantalab, and Tope Sherkhania, sensing the impending storm. The Anantnag riots were not an isolated event but a precursor to the full-scale exodus of 1990—one of the darkest chapters in Kashmir’s history.

Keeping the Memory Alive

Nearly four decades later, the 1986 Anantnag riots remain a painful yet often overlooked episode. Some may question the relevance of revisiting these events, but remembering history is crucial—not for vengeance, but for understanding. Only by acknowledging the past can we hope to ensure that such tragedies are never repeated. Some of the attached newspaper reports from that era reveal significant yet overlooked truths, backed by authentic evidence. Through this modest effort, Kashmir Rechords seeks to revisit and shed light on those forgotten times.

- Readers are invited to share their experiences and perspectives on the 1986 Anantnag riots in the comments section, ensuring that this chapter of history is neither erased nor forgotten.